|

Over 30 years ago, Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and the late Steven Izenour wrote Learning from Las Vegas, a revolutionary case study that opened the world's eyes to vernacular architecture and iconography-the "ugly and ordinary" structures and signage born to satisfy the needs of regular people, not architects. Today, the Las Vegas they wrote about no longer exists, but the ideas brought to the fore by the pioneering architects, who once famously declared "less is a bore," now inform the urban planning and construction of areas intended for mass use. I recently spoke with Scott Brown and Venturi about what's transpired in Las Vegas architecture since the book's controversial debut, the lessons learned from their own research, and their opinions on the emergence of Lifestyle Centers, a re-imagining of the shopping mall as an outdoor environment based on the concept of a traditional small-town Main Street.

Melissa Urcan: I would first like to ask you about the weight of Learning from Las Vegas, now almost 35 years old. Do you feel tied to the association of your work to this book, or is it something you continue to draw from?

Robert Venturi: Since then we have written an essay called "Las Vegas After Its Classic Age," which emphasizes that Learning from Las Vegas in the context of now is completely historical. If you had written a book on the Renaissance in Florence, it would have taken maybe 100 years to say, "Oh that's historical." Now you can say 35 years have gone by very fast. But Learning from Las Vegas is still relevant in many ways, such as in its recognition of the relevance and significance of iconography and signage more than of space. Las Vegas got us in a lot of trouble, but we learned a lot from it.

MU: The Strip in Las Vegas appears to be where you spent the most research time. In this book you had the premonition of the building and sign eventually merging. Did you have any idea how big the entire city would become?

Denise Scott Brown: We did concentrate on the Strip, but not only on the Strip. We studied patterns of land use throughout Las Vegas. And we mapped all the strips of Las Vegas, not just the famous Strip.

RV: In the essay "Las Vegas After Its Classic Age," we say the obvious-that the Strip evolves into the Boulevard. The former Strip is now officially "the Boulevard." I love the use of the word "scenography"-in a sense Las Vegas is now City as Scenography; it's a Disneyland. Most cities are to some extent scenographic, but few are as explicitly theatrical.

MU: Does this type of scenography make it irrelevant to you? Or do you think it is pointing to something else in society? Do you think people are looking for this type of scenography?

RV: I think there are all sorts of ironies concerning people looking for too much urban cohesiveness, for urbanity that is too neat/correct. There is also the irony that Americans hate signs; we are enormously afraid of being vulgar because of our signs in our cities, and of being thereby materialistic, commercial, and all that. On the other hand, we Americans are geniuses when it comes to signage-commercial signage: we are as good as the Byzantine artists who composed mosaic murals and the stained-glass artists of the Gothic period and the Renaissance muralists of Italy!

DSB: You are also asking if [casino/hotel tycoon] Steve Wynn's Las Vegas is relevant. I think Wynn saw something changing in America and reacted to it, and in doing so, has done very well. I am not sure people like us can love the new Vegas. It doesn't hit our funny bone, our crazy bone, in the same way. Is it irrelevant? People's choices and patterns are always interesting, but is it relevant to our work? For me, personally, no.

MU: It is surprising to me how similar the outskirts of Las Vegas are today to so many other cities, but all developed within a very short time. I have been looking at this development in commercial construction, particularly the recent phenomenon of the "Lifestyle Center."

DSB: We have done a considerable amount of planning for main streets in small towns and neighborhoods over the years. We recommend that they hold their own against the suburban malls by building on their unique strengths. Main Street is different from the mall; for one thing, it has sky above it. Also, its unique old buildings lend character and atmosphere. Developers of Lifestyle Centers seem to realize that Main Street has something. They are a good model for study in the same way the Strip was in 1968. Like the Strip, they are different from the typical in the scale and speed of their growth and in the fact that they are not usually overlaid on historical patterns. And Lifestyle Centers in the Las Vegas region are also affected by the style of Las Vegas.

MU: There seems to be a continuing pattern, a gentrification of areas and Main Streets beginning with the discovery and marketing of a newly "desirable" living area, which then leads to higher land value pushing out the stores that cannot compete. Concerning these Lifestyle Centers and New Urbanism, this newly clean Main Street seems to be a model that they would like to create instantly.

RV: We are not very happy with the New Urbanism-although in Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture I said, "Main Street is almost all right," which [in 1966] was shocking. One thing I would like to interject: the element of community is really important to us. People are wanting more and more to connect with community, and a communal lifestyle can connect with scenography and iconography. Main Street can be an iconic element of community.

MU: Specifically, why are you not happy with New Urbanism?

RV: I feel the New Urbanism doesn't acknowledge, or doesn't sufficiently acknowledge, the broad range of urban and regional social problems of America today. Nor does it deal with the complexity of urban programs of today. For me it's too pure, and it veers too close to the sentimental.

MU: Concerning people's needs, I recall in Learning from Las Vegas you mentioned a need for intimacy satisfied through Disneyland's Main Street and its 5/8 scale. What do you think it is about the specific historical styles, such as Victorian, Georgian, and Greco-Roman (used in these Lifestyle Centers and Disney's Main Street), that people find so appealing or familiar?

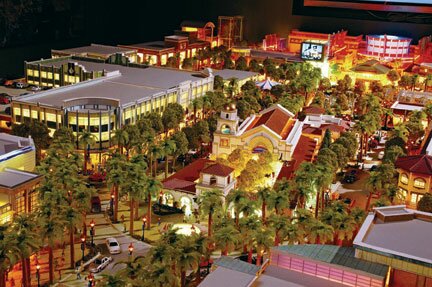

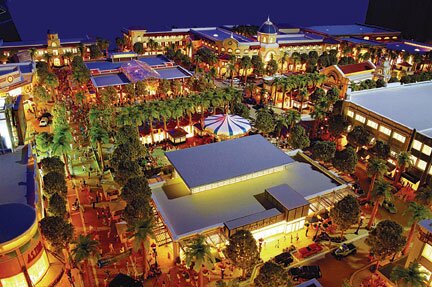

Town Square Las Vegas, A Retail Lifestyle Destination (model, two views), opening Fall 2006

DSB: Disney built Disneyland because he was looking in the LA suburb where he lived for someplace he could take the kids on a Sunday afternoon-for a Main Street. But you don't have to live in Disneyland and if you did, its 5/8 scale and sentimentality would be frustrating. Yet residential life needs a setting and sometimes people want to redefine themselves through their setting.

MU: Do you think that architects build for architects and developers build for the people? Or are developers just developing a brand to market, a lifestyle to sell?

DSB: I think developers try to build for what they think the public will buy. Whether they have the analytic tools to tell what the public wants is difficult to know. And whether their success is due to a correct analysis or to a shortage of housing is hard to tell.

RV: Architects' architecture is often an intrusion, although planners are often puristic.

DSB: I am not sure the developers are that much better. A successful record of sales doesn't show whether they are building housing that is really satisfactory or that is just good enough-whether people are putting up with the parts they don't like.

MU: It's interesting that you mention "good enough," as I think many architects believe the "public" would choose something else, or more important, something better, if they had the choice.

DSB: Architects do believe that. Lou Kahn said we didn't know we needed a Beethoven symphony until Beethoven gave us one, and there is logic in that argument. But it should not be used to oppress the lives of vulnerable people; for example, those in public housing. We fall on both sides of the issue. On one hand, we too are passionate architects, and we too feel we know something, have an expertise. On the other, we believe we should not use our expertise as a blunt instrument. Working for an individual client whom we meet face-to-face, we can say, "We just can't do this," explain why, and argue the problem through. Working with an individual you can duke it, maybe losing the job, maybe convincing her or him. If the result of the debate is something greater than either expected-then that is an ideal relationship. The big questions arise when architects work for a client they don't meet, one that can be known only through statistics, or that won't be there until the project has been built. You have then to work out how not to oppress this unknown future client. And over the life of the building, it will perhaps be used by 100 clients, 200 clients. What about the architect's duty to the client that is 100 years away? How much do you owe that person as opposed to the one who has given you the project and the program today? ?

|